EHF & Zealandia

EHF & Zealandia

Lessons in Hope and Interconnectedness with Jane Goodall

Insights on restoring the ecological realm from the world’s most loved conservationist. By Alina Siegfried

Dr Jane Goodall was a in a taxi to Heathrow Airport, when the cab driver caught her eye in the rearview mirror. “I know who you are”, said the driver. “You’re just like my sister, you think animals are better than people”. He went on to talk about how hard life was for him, and how Jane would be better placed putting her energies into caring for people over animals. After giving the driver time to air his frustrations, Jane told him about her work in wilderness areas in Africa. How she had witnessed a transformation in people who had learned that through protecting habitats for wildlife, they were also safeguarding their own futures. She talked about witnessing animals helping humans in trouble, and about the interconnectedness of all life.

When they got to the airport, the driver didn’t have the correct change. Jane told him to donate the ten pounds owed to his sister, who volunteered with the local SPCA.

Upon arriving back home some time later, Jane opened a letter from the man’s sister, thanking her for her donation, and also asking “What have you done to my brother??” — He had begun helping his sister with her volunteer work.

It is a testament to the power of stories, conversations and everyday interactions to shift minds and hearts. It is with this intention that the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) is on a mission to create a critical mass of people around the globe working to change the world.

On a blustery Autumn morning, we convened Fellows and community members of the Edmund Hillary Fellowship (EHF) to meet with Jane for a roundtable discussion initiated by Melanie Vivian, CEO and Co-founder of Jane Goodall Institute New Zealand, who has been a long time friend of EHF. We have come together to discuss approaches towards solving the complex challenges of our times, how we might create the most impact, and how to empower a whole generation to be kaitiaki (guardians) of our natural world. Fittingly we have met at Zealandia, Wellington’s award-winning eco-sanctuary which has helped bring a number of bird species back from the brink of extinction, to be thriving in the Wellington region once more.

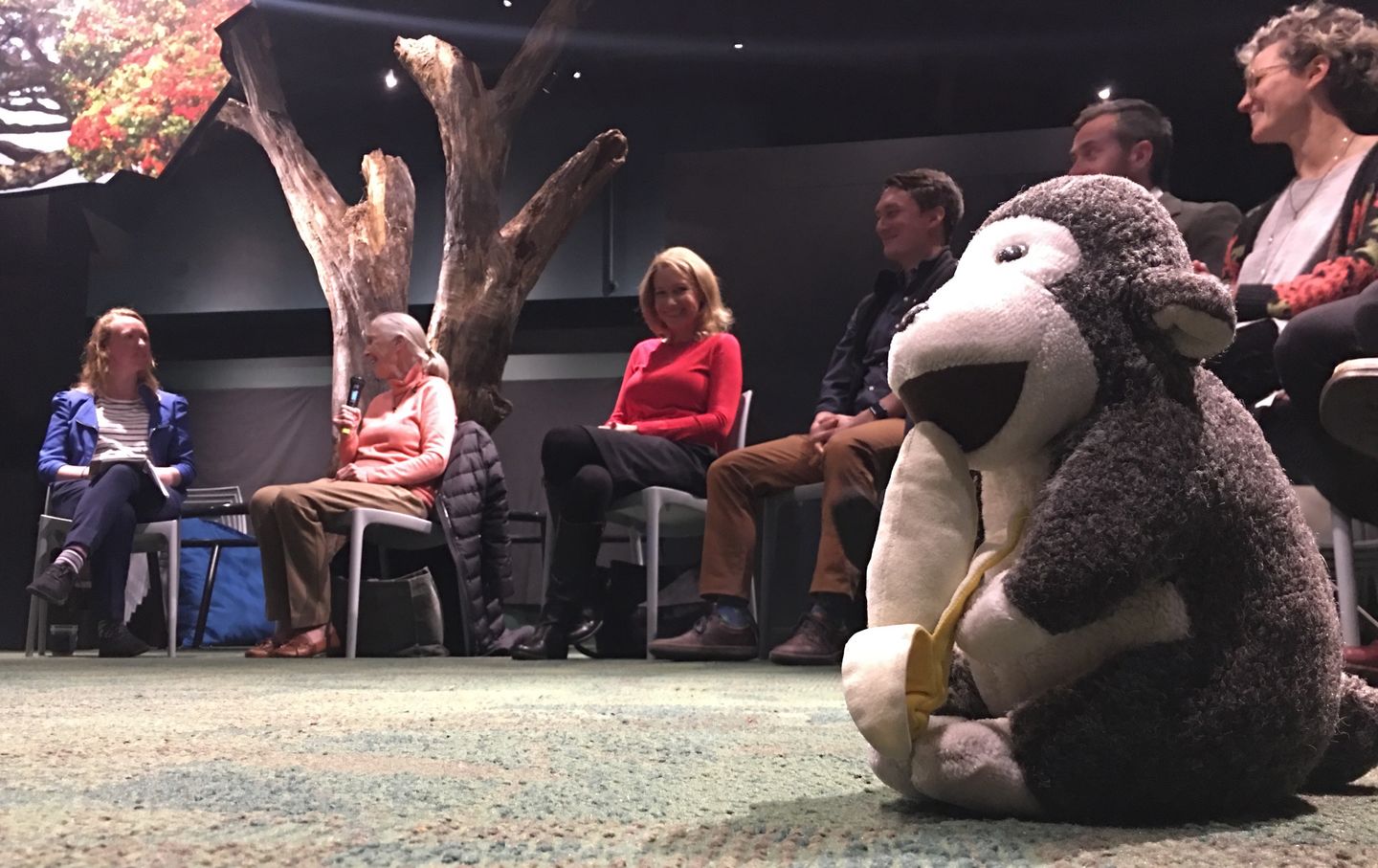

We meet in a beautiful upstairs room with a real pohutukawa tree trunk and hanging splashes of crimson foliage, while informational tiles about threatened species adorn the walls. The mottled green carpet mimics the forest floor, and in the centre of it, sits a stuffed monkey eating a banana. Called Mr H, the toy monkey was given to Jane 29 years ago on her birthday by a blind friend who thought he was giving Jane a toy chimpanzee — yet the monkey has a tail, while chimps have none. Despite being blinded in a crash, Jane’s friend fulfilled his dream of becoming a magician, and so Mr H travels with Jane wherever she goes as a reminder of the indomitable human spirit.

But today, he sits in the middle of the room, holding court. As if the speaker of our little parliament, he watches over the discussion, as if holding us to account as Jane imparts her hope and wisdom across a number of themes.

The importance of working with people who think differently

Jane is asked about how we can deal with the inertia imposed by the predominant systems that make up our societies and economies, and how we can deal with the seemingly insurmountable task of changing the status quo. The recent Environment Aotearoa report, released by the Ministry for the Environment paints a grim picture of the state of our nation’s biodiversity, and is cause for widespread alarm.

She responds that there are so many opportunities, every day, to engage across the spectrum. The JGI New Zealand recently pulled together a number of non-governmental organisations to sign on to the Aotearoa Deal for Nature, also signed this week by Jane. Together they have been able to identify 20 steps in a roadmap for urgent action across a number of areas.

Jane adds that sometimes you need to engage with people who think in vastly different ways from yourself. Last year she attended the World Economic Forum in Davos, despite being reluctant to do so, being more at home speaking with action-driven community groups than global scale forums. But the importance of having a voice there to represent nature won out, and so she went.

Many large corporations are beginning to change their behaviour to be more sustainable and socially conscious in their operations, largely due to public pressure and consumer demand.

A strong focus of the work by 34 global chapters of the Jane Goodall Institute, and Jane’s personal passion, is their sustainability and citizenship programme Roots & Shoots, where young people are empowered to undertake youth-led projects, for the benefit of animals, people, and the planet, and to inspire compassionate leadership. As many of these children have parents working in government or as CEOs, Jane explains that we can often reach older generations through their kids.

She is careful to add that we must not be hypocritical in how we call for change — many of us fly often, we drive our cars, and we use products that are made by the companies who routinely come under fire. Rather than criticise and point the finger, her recommendation is to reach the heart.

The power of stories to harness empathy

As a young researcher, Jane was told that in order to be a good scientist you had to shut down empathy and compassion, and to be objective. The popular thinking back in the 1960’s and 70’s was that animals did not experience emotions. It’s a notion she whole-heartedly rejects, viewing all life as intelligent with the capacity to feel emotion. There is indeed now scientific evidence that when animals have experienced loss and show signs of grieving, the same parts of the brain are firing as in our own when we experience sadness.

While the science is important, Jane knows first-hand the power of a good story. After all, scientists have been warning of severe climate change since the 1970’s, yet it is the stories that have shifted narratives in recent years.

She has stood with Inuit elders in Greenland who recall the days when the ice on the glaciers never melted, even in summer, but where she saw them now flow, and then with indigenous peoples in Panama, experiencing rising water levels. She’s visited places where the droughts have been so severe, that farmers need to kill their livestock. In the aftermath of hurricanes, typhoons, floods, it is the first-hand experiences and stories of people who have been affected that gain the most traction in inspiring people around the world to take action against climate change, and the destruction of the natural world.

The importance of having difficult conversations

One of the EHF Fellows in the room asked Jane what our biggest blindspots are as environmentalists. She is quick to respond that human overpopulation is an issue which we are largely unwilling to discuss as a global society. War, pestilence and famine no longer kill off human populations at the rate that they once did and many of us live unsustainable lifestyles, while economists tell us that infinite growth is possible and indeed, desirable. The reality, however, is that we live on a planet with finite resources.

These conversations are difficult to have. People rightly regard human life as sacred (as is all life), and so conversations that suggest we should not reproduce at our current global rate are understandably contentious. They are also often viewed through a privileged, westernised lens that does not take into account the complexity of reasons why large families are desirable in less wealthy nations.

One solution that has been adopted across Africa and Asia, is to focus on women’s education, recognising that education is a great form of birth control. Development organisations are offering scholarships for girls to stay in school, while others provide microcredit to women.

Being at Zealandia, the subject of invasive alien species control came up — another difficult discussion to have, particularly in New Zealand where the rate of extinction of our native birds, who evolved without any mammalian predators, has brought about the use of controversial methods.

While it is necessary to control these non-native species to ensure the survival of our native bird species, Jane’s (and JGI’s) view is that we must do so as humanely as possible, and without the vilification of species or celebration of their death, particularly for our young people who may be more susceptible to the underlying message that there are “good animals” and “bad animals”. She detests hearing species such as possums, rats and stoats referred to as “pests” or “vermin”, reminding us that it was us who brought them here in the first place. It’s not their fault they find themselves on these islands where they find such easy prey.

“We ARE the invasive species.” — Dr Jane Goodall.

Zealandia Chief Executive Paul Atkins added that the biggest transformation that has paved the way for a comeback of native bird species is a societal one — people have seen the return of tui, kereru and kaka, and are beginning to realise our responsibility as a species to rectify our wrongs from the past.

Small actions add up to big changes

The hallmark programme of the Jane Goodall Institute worldwide, the Roots & Shoots programme began with 12 high school students coming together at her house in Tanzania, with concerns around poaching, illegal fishing, stray cats and dogs, and the plight of children living on the street.

It’s a common misconception that the Jane Goodall Institute and Roots & Shoots groups only care about animals. For virtually every kind of problem that we face, there is a Roots & Shoots group working on it. While the institute has been criticised for being “too scattered”, Jane maintains that the strength of the institute and associated Roots & Shoots groups is that they are diverse.

From preschools where children take conservation values forward into their adult lives, to retirement homes where older folks gain a new lease on life, there are now Roots & Shoots groups operating in 60 different countries. Partnerships with other organisations help take the work out into the world. All operate with a philosophy of bottom-up, grassroots action, with members deciding what is the most effective way for them to bring about change in their unique communities and environments.

It is this multitude of different kinds of action that can lead to large-scale change. Sometimes these actions are small and very local, but can be hugely powerful.

Jane shared a story of group of 8–12 year old students in the Democratic Republic of Congo, living in the east where the fighting is most severe. The students came to realise that a nearby clearcut hill was traditionally considered sacred, and they wanted to reforest it. The coordinator of their group went to the local militia to ask permission. The commanding officer thought it was a stupid idea, yet sent four soldiers with AK47s to accompany the band of 15 small children on this unlikely mission to plant trees.

After 15 minutes of lounging about in the grass, a little girl began to cry, frustrated that the sun-baked earth wouldn’t budge. A soldier laid down his gun and helped her plant a tree. Within another 15 minutes, all of the soldiers were helping the children to plant trees. A powerful metaphor for what could happen if more of us were to lay down our arms and take up spades.

Small actions, big changes.

Finding balance

Many of us who are passionate about ecological restoration and sustainable living feel the urgency of the global social and environmental challenges that we are facing, which call for an “all hands on deck” approach with a focus on immediate action. Yet, it seems like without a fundamental shift in mindset that places humanity squarely within the realm of “nature”, and valuing quality time spent in connection with nature and community, that none of the urgent work we do will have the required impact.

One member of our group asked Jane about the question of balance — while serving as an inspirational mother figure to millions, how does she balance her advocacy with the need to look after herself and her family? Her response was to simply to make the time. When her son was young, despite her busy work with chimpanzees, she wasn’t away from him for a single night during his first three years of life. She worked with chimps in the mornings, and spend the afternoons with her son.

Jane currently spends 300 days a year travelling, and only takes off three weeks per year. An impressive feat for a woman of 85 years, and one that she pulls of with immense grace, humility, and a healthy dose of humour — she joked that when you’re older, you have less time left, so you have to work harder.

Remaining hopeful

Perhaps the most important takeaway of the day, is that we must hold on to hope. It’s no coincidence that many of Jane’s books have the word “hope” in the title.

Much of the world’s media is perpetually focused on the negative, but there is so much good going on around the globe every day. Dedicated people are achieving amazing things. With the intention of celebrating these successes and inspiring others into action, Jane and the JGI share these stories on their blog.

A question was put to Jane about how we can inspire young people who are already struggling with so many other social pressures and problems, to care about other issues that are not immediate to their individual circumstances. The example was given that in New Zealand, we have a disgraceful rate of suicide amongst young Māori, and that asking them to care about environmental issues was like “asking for investment from an account that’s already overdrawn.”

While it might seem counterintuitive, Jane explained that she has seen time and again people who live in incredibly difficult circumstances become empowered and gain a new reason for living by becoming involved in Roots & Shoots groups. She knows of would-be suicides that were averted after people attended her lectures. She told the story of one young girl in China who told her “I used to feel like I was nobody, but now I realise that I am somebody, that I can make a difference.” She recognises that it is harder in urban areas, where people are more cut off from community. Yet the connection and sense of purpose provided by these groups, helps people to hold on to hope, and realise that they have a future.

“The reason I travel 300 days a year, is that people come up after every talk and thank me for inspiring them. What’s the point of fighting, raising money and exhausting ourselves if we don’t have hope for the future? My job is to give people hope.” — Dr Jane Goodall

New Zealand has an opportunity to catalyse a massive transformation and become a world leader in prosperity for animals, people and our shared environment. As Jane reminds us, we can achieve so much when we work together.

As we finish up our discussion and embark on a walk around the sanctuary to listen to the native birdlife that is now flourishing, I watch as Jane pauses for several minutes to observe a tui that is singing up a storm, as if to thank her for her work. As we quietly observe, I’m struck by the manner in which Jane engages in her activism. She speaks with a gracious simplicity, encouraging us to find the answers within ourselves. Faced with complex questions, she seems almost amused at our tendency to overthink things, and gently reminds us that if we look closely — deep down — we already know the answers to most of our questions.

When it boils down to it, the answer is to have hope, care about something, and then do something about it.